Understanding the role of cities in the Covid-19 pandemic can help us build a sustainable and equal future, David Simon writes in the Conversation.

From its origin in Wuhan, China, COVID-19 has spread to become a predominantly urban-focused pandemic. Although much data on the pandemic is still unavailable, it is clear that urban areas have been at the epicentre.

We can seize this opportunity to improve how we build, organise and use cities. To do this, though, we need to look more closely at the urban spread of coronavirus to understand its impact on existing inequalities. We can also learn lessons from the past impact of epidemics on the most vulnerable urban populations.

It is already becoming clear that certain groups are being affected unequally. The poor and ethnic minorities are particularly vulnerable. Patterns of illness and death reflect urban social and economic geographies. Attention has focused on shielding the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions, defined as being most at risk, but the reality is more complex.

Inequalities caused by ethnicity, religion and income often overlap, so that the proportions of elderly and vulnerable people vary by community and neighbourhood. A potential genetic factor in immunity is being investigated. However, the combination of social, economic and demographic factors together with the urban environment probably accounts for many of the observed infection patterns.

Unequal patterns

Minority groups are often over-represented among the urban poor. This means they are more likely to have poor diets, get inadequate exercise and to be overweight. This exposes them disproportionately to diabetes and other chronic cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, putting them at high risk.

Poor people also inhabit the lowest quality housing and areas of a city. They live at the highest densities and in the most cramped accommodation. These areas have higher air pollution levels, and poor quality or inaccessible utilities and services. They often have the smallest areas of open public spaces.

Green spaces such as parks have been recognised as vital for human health. But the people who need such spaces most – those without private gardens – have the least access. Parks serving these people have also come under greatest pressure during the lockdowns. Closing them rather than ensuring that people using them follow social distancing guidelines exacerbates the problem.

Risks of overcrowding

COVID-19 and similar viruses are passed on through contaminated moisture droplets from sneezing, coughing or heavy breathing. This means that people living in the same household as someone with the virus have a high likelihood of contracting it.

Almost everywhere, including the UK, large families living in the same household, including members of different generations such as grandparents, are more common among the urban poor and certain minorities. Shielding, self-isolation and social distancing are almost impossible to do in these circumstances. This highlights both the elevated vulnerability of those most at risk and the futility of preventative guidance that ignores these realities.

Institutions housing large numbers of residents are also potential transmission hotspots. Retirement and care homes present particular challenges – and the news is filled with the grim toll there.

Many cities in low- and middle-income countries will face even greater risks should the virus gain a foothold in urban shantytowns and high density areas. Strict preemptive lockdowns have been implemented in India, Kenya, South Africa and elsewhere, before the virus could gain a foothold. If this were to happen in the likes of Dharavi (Mumbai), Kibera (Nairobi) or Khayelitsha (Cape Town), the consequences would be horrific.

Future concerns

Hasty, reactive measures, such as closing all wet markets before the actual source of the virus is known, may prove misguided. It is urgent to think critically and to engage with the underlying issues identified here rather than superficial symptoms. Experience from previous epidemics and pandemics, such as bubonic plague, smallpox, cholera or influenza, can also provide important lessons.

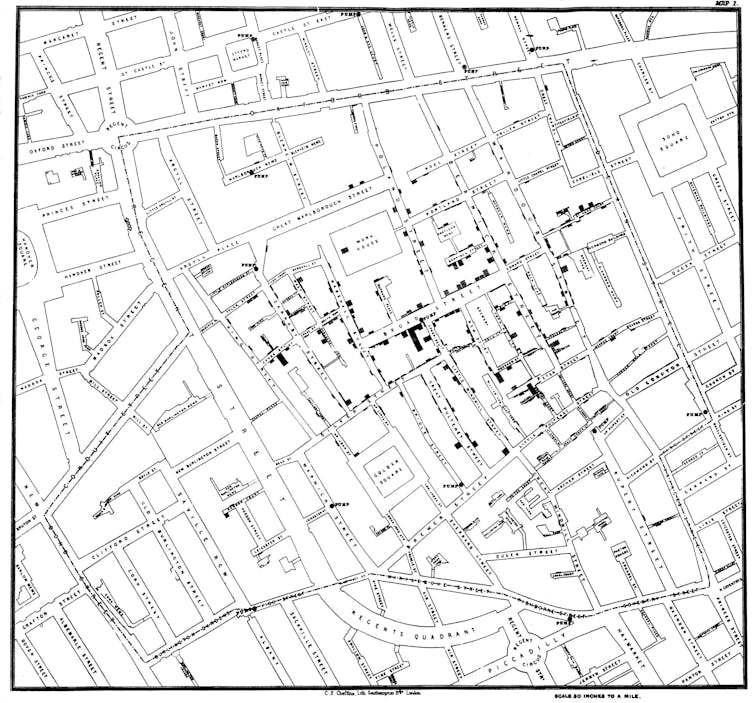

Map of cholera cases in London, 1854, created by Dr John Snow, which linked the outbreak to the Broad Street Pump water supply.John Snow/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-ND

One classic example is the place of 19th-century European cholera epidemics in stimulating the construction of piped water and sewerage systems. This followed the discovery in London that one contaminated drinking water point was the source of the 1854 outbreak. By contrast, in Hamburg, inaction after the 1873 cholera outbreak due to inertia, short-term self-interest from the rich and divided medical opinion led the city to suffer an even worse epidemic in 1892.

Health-driven urban renovation and infrastructural improvement can, however, also be implemented for political or sectarian motives. For instance, an outbreak of bubonic plague in Cape Town at the turn of the 20th century was blamed on the poor African victims by the colonial government and settler community. The outbreak was used to impose forced segregation. In the name of sanitation, the first urban “native location” was constructed outside the main city, where its population was easy to control.

Similar concerns are already being heard about wider potential political surveillance and control. Some governments have quickly implemented the use of mobile phone apps for COVID-19 contact tracing.

We have a unique opportunity to work towards fairer, more sustainable cities in the wake of coronavirus. Emergency government economic support packages must be used proactively. Global plans such as the New Urban Agenda, endorsed by the United Nations in 2016, can steer a shift to green, circular economies. And we can build robust resilience against diverse disasters and climate change – the long-term crisis we already know is looming.

David Simon, Professor of Development Geography, Royal Holloway

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.